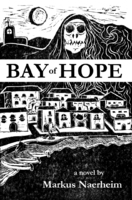

On the Rocks

Photo by Markus Naerheim

It was nearly midnight and Henrik was blissfully alone. He was on summer break at the family cabin, which provided the perfect setting for him to pursue his research in peace. The cabin was located on a peninsula between the fjord and a small bay. The fjord was wide enough so that the houses on the other landmass were not visible. During heavy storms, the far shore would disappear completely. The bay itself was surrounded by mountains on all sides. The peaks of the mountains were a blend of blue-gray depending on the cloud cover, and even appeared purple in stormy weather. Below a certain altitude, they were shrouded in green scrub that gave way to a thick skirt of forest, which extended nearly to the waterline. The forest also had its moods. On warm summer days, the trees were light green and distinguishable one from the next. During a storm, they huddled into an opaque dark green or black mass for protection. In the north, the weather changed like a man’s mood might change with his fortune; its arrival could mean the death of a fisherman out in the fjord, or the difference between a pleasant hike in the highlands, and a hastily built fire in the shelter of a cliff.

That evening Henrik sat on the veranda, enjoying the pale northern sun. He ignored the books scattered across the table and shut the glowing screen of his laptop. He had put in his workday and now it was time to relax. In the bay, the water was smooth like a plate of glass and pleasant to the eye.

In afternoon, after lunch, Henrik went to sharpen an old rusted scythe at the Olsen’s farm. It was a good excuse to escape from his work and take a pleasant bike ride around the perimeter of bay. His family and the Olsen’s had lived in that bay on the fjord for many generations. Their great grandfathers had known each other and if Henrik did not pay the Olsen’s a visit, they would certainly be hurt. The news had already traveled that Henrik was staying there for the summer and they were no doubt eager to see him.

When Henrik arrived, Mr. Olsen sharpened the scythe on his grindstone before inviting him in for coffee. The Olsen’s didn’t get many visits anymore. Most everyone had moved away and they were eager to hear the news about the family and Henrik’s life in the capital. Mrs. Olsen stuffed him with cookies and cake and he tried his best to entertain them with the news. When he left, Mr. Olsen gave him a flask of moonshine and promised to come fishing with him. Though he liked the Olsen’s, and they had always been kind and generous with him, he was glad to be alone again on the veranda, sipping a beer, and watching the ocean. Tomorrow, he would cut the grass on the hill below the cabin. None of the family had been out to visit since last summer and the garden was overgrown. It was the sort of work a young man did to help out his grandmother, though at eighty-five she had insisted on scrubbing the deck and the floors by hand before his visit. Still, tomorrow was tomorrow, and now it was time to fish.

Henrik found it refreshing to get away from the bustle of the capital where he juggled a busy schedule of class and work. He did not miss the winter commute from his suburban apartment to the university through the darkness, rain, and snow. Nor did he miss his weekend social habits, in particular the obligatory appearances at this or that café, club or restaurant of the moment. No, there was nothing like a summer in the North for a little peace of mind. Now he followed one routine: up at sunrise to fish, writing during the day with an intermittent nap on the couch or a walk in the woods, and fishing again at dusk. His body was by now accustomed to sleeping the few hours of semidarkness of summer.

He put on a wind-breaker and grabbed his hat. He undid his belt and slid his fish knife into place on his hip. In one pocket, he put his box of favorite lures: in the other, Gustav Olsen’s fifth of moonshine, “for when it gets cold in the boat”. Gustav Olsen and his father had grown up together during WWII when the German’s had anchored at the mouth of the fjord and set up camp on the peninsula. What a time that must have been. Now, the pain and suffering of war was gone without a trace.

That day Henrik did not plan to take out the boat. He would fish on the outer cliff where the seafloor dropped off into the trench of the fjord and the big fish hovered in the depths. Whether in a boat or on the exposed cliff, the liquor would taste good all the same. He was in a good mood as he collected his rod and put on his boots. He took a half-eaten chocolate bar and put it in his pocket. He left the cabin and set out on the narrow trail by the shore. He cut between the aspen trees and crossed the main road to other side of the peninsula. The dock was empty. The last ferry had come and gone and would not be back until the morning. It was the most direct route from north to south in the country without taking a major detour inland. It was also the only connection to the main town for the local inhabitants on their scattered farms. It was a forty-five minute ride to cross the fjord. Henrik took the ferry once every week or so to get supplies. He did not need to go that often but for his vice for chocolate, beer, and the newspaper. Back at the cabin he had the necessary staples for an extended stay: a sack of potatoes, crackers, a chunk of cheese, jam, coffee, eggs and butter. And plenty of fresh fish from the ocean, whenever he chose to catch it. It certainly could have been worse, but probably not much better.

He crossed the road by the ferry dock and followed along the Bordahl’s pasture with the forest on his right. It was not dense forest, like the pine trees that rimmed the far side of the bay and climbed the mountain. The peninsula was too exposed and the earth was poor enough that it only supported some aspen trees and low-lying bushes. Inland, the forest absorbed the land and alternated with fields of grass and grain. He walked on picking his way between the scraggly trees, careful to keep his rod point up. Once his lure dug painfully into his finger and he inadvertently tugged it deeper before getting it free. The landscape grew rocky as he neared the cliff. He found the well-worn trail that he remembered from his childhood and followed it to the shore. The trees parted and he found himself on the cliff face that sloped steep and convex into the water. It was closer to low than high tide. The water started some three meters below. At low tide, depending on the moon, it would drop another two meters. At other times, the tide would come within a meter of his feet.

He remembered when he was younger his grandmother would warn him not to fish on the cliff. The currents were especially strong, and there was no way to get out again if one fell in the water. He smiled to himself at all his grandmother’s good advice that he had ignored. He remembered how he would refuse to put on the various ugly hand-me-down sweaters and jackets, wool caps, and hand knit mittens that she had forced on him when he went out fishing with his grandfather. Now he could admit she was right about keeping warm, fashion or no fashion.

Some of the best moments of his childhood were spent fishing with his grandfather. His grandfather, that laconic man who smoked hand-rolled cigarettes and who called spaghetti “mafiosi”; that grandfather who had sailed the world in the merchant marine and who had lain bedridden with malarial relapse several times a year; who was in addition a first class alcoholic and who eventually died of cancer, God rest his soul. Henrik would never forget his grandfather’s tanned and weathered face, sailor’s cap on his head and cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth, as he stared out to sea with his impervious black eyes. He would always remember his grandfather with his hand on the throttle driving the motorboat into the wind of the open ocean to the fishing ground by the seamount that only experience could find. In his grandfather, Henrik imagined a better past when man saw clearly his dependence on nature. Henrik admired his grandfather greatly and regretted that he had died before he could do him proud with his own achievements. The only time Henrik had felt his approval was that summer when he hooked into a record-size cod and fought it for nearly an hour with his sixteen-year-old hands until its blank alien face came to the surface and they nearly capsized the boat trying to get it aboard.

“That fish is bigger than you. Watch out so he doesn’t swallow your arm.”

The grin that split the man’s usually blank face was a moment forever sketched in Henrik’s memory.

But then the joy of acceptance passed just as quickly when his grandfather casually stabbed his knife into the fish’s brain while it thrashed out the last of its life. As Henrik fought to keep his emotions down, it was clear that he did not understand the boundaries and importance of life and death. Perhaps it was from his grandfather that he had learned that to be emotional about death was cowardice.

Still, how could he forget the pity he felt for the small shiny pollack juveniles that were thrown carelessly in the hull of the boat, flap-jacking on the wooden hull like curious bullets in the dance of asphyxiation. It was perhaps the purity of their eyes, and the beauty of their form that made it so upsetting that they suffer only to be thrown to the birds or dumped overboard by the boathouse when they returned. It was also the quantity that turned his stomach. Then there was the time grandpa tossed a lone fish back into the water and he had circled like a submarine with his nose out of the water brain-damaged, insane and hopeless. Henrik remembered always how his compassion fought with his pride in the desire to grab the juveniles by the handful and fling them into the black safety of the ocean. But then he did not want his grandfather to think he was weak or a city slicker disconnected from the food chain. The law of the ocean was life and death. What a man caught he could waste. But then maybe that truth had died with his grandfather’s generation.

He wondered how his grandfather must have felt on his deathbed. In the hospital, he no longer appeared to be a monument to tradition looking ever toward the distant hope beyond the prow of his vessel. To Henrik he had become transient like the elements he navigated, he was decaying like seaweed exposed by the tide, another bit of life tossed on the shore to whither away and be forgotten. But Henrik did not forget. He carried something of the man inside himself, inscrutable as it was.

In the early stages of death, his grandfather’s eyes still glowed with all the emotion that was frozen from his features. Later, he gasped for breath and stared not at the future but oblivion. He was no longer charting the unknown, but drifting by the force of mysterious unmanageable currents. Henrik wondered if his grandfather had felt fear in death, the same fear of the cartilage-faced cod, with its staring eyes naked and obscene in the alien world above the water. Were humans as obscene with their four awkward limbs below the surface? He could not be sure.

When he fished on the cliff, he thought of his grandfather and his father fishing there before him. He thought of tradition and the past and knew he was but a continuation of what had been. He had returned to the place his father had left for a better future, and he would continue to return there, to the nostalgia of the past. He was not fishing for need but in contemplation. He would catch something, but it was not the catching that mattered, rather the anticipation and the unknown they lay at the end of the line where he dropped it into the water. The shiny spoon with the blue stripe, a hand-me-down from his father, the blue paint nicked and flaked from teeth of fish dead and eaten, fish who had fought and died, was his feeler into a world and a past he had always admired; it was a connection to something vital that he felt was missing from his life in the city, from the artificiality and empty talk of the bars, and the hoop-jumping and cynical networking of his graduate career. It was, in short, a peaceful moment spent in contemplation of the truth of man’s existence.

If I catch a fish, I eat. All I have to do is catch a fish. There is really nothing more to life than that, he thought. How we choose to make life complicated, rushing around day in and day out, to jobs distant from our communities, and our own character. Certainly, there were people who pursued careers of their interest and for that they had to leave the countryside and go to the city. Obviously, professional careers required a university education. He had been studying his whole life and mostly he had not worked but lived off government loans always becoming more educated. Soon he would have a Master’s degree and then he would no doubt go for his doctorate. But where would it end and when would he actually provide some benefit to his society? There were men who had started working straight out of high school and who had kept the machinery running while he sat with his nose deep in books dissecting the why and how of real life. Shouldn’t they find him ridiculous?

Henrik knew that he could never renounce his artificial and ideological life and the city that allowed his sort to survive. He was not a practical person, and truthfully he was not in tune with the natural world. But if that were the case, why did he look so forward to leaving the city and spending the summer alone in the North with only the ocean and the mountains for company? Was it only enjoyable because he did not have to remain in isolation like the Olsen’s? How different was he really from his grandfather at his age, pictured in black and white photos standing by a camel in the Moroccan desert, or sitting with a few shipmates under a palm tree on a South American beach?

With these thoughts in mind, he released the safety on his rod, held the line to keep the spoon from dropping to the rock and sliding down into the water, and swung his arm back in an arch; with great satisfaction, he threw the small metal weight out into the open ocean. He watched the filament of line unwind from the reel to where it disappeared in the pale light of the sky. He focused on where he thought the lure might land. When it struck the water his eyes shifted away from that imaginary location to the ripple where the lure broke the surface of the water with an authoritative “plunk”.

Admittedly, his tackle was not ideal for the conditions. The rod was strong enough, and the drag on the reel could certainly be adjusted, but then the line was only five pound tess, better suited to fishing in the bay where the fish were generally smaller. His experience there made him wary of the bottom, where he had snagged up all manner of seaweed, jellyfish and stones that significantly thinned his lure selection. Low tide had proven a particularly hazardous time to fish.

Henrik thought it more of a disappointment then a joy to catch a cod in the bay for its small size and the nuisance of having to inch down the sloping bank to get it loose from the tangle of seaweed and jerk the hook free from heavy cartilage of its jaw. The problem with cod, aside from the fact that they hung like dead weight on the line, was the fact that they inhaled food and it was often the case that the hook would be buried deep in the fish’s stomach, so that he had to jam pliers down its throat, and open the fish’s jaw to an unpleasant one hundred degrees plus to get his fist inside. Sometimes it was hopeless and he would have to either rip the hook out and condemn the fish to death, or cut the line and let the fish carry the metal as a souvenir. No, sometimes it was better to not catch anything at all if it wasn’t what you were looking for. In fact, when he saw small fish pursuing the lure in the shallows, he would jerk it away faster than they could swim, to spare him the trouble of catching them. Cod, he thought, they’ll eat anything so long as it shines. They like gold the best, and pollock, they like silver.

Henrik preferred fishing for pollock from shore, because the cod he wanted, the old faithfuls, they sat down deep and contemplated the meaning of life. No, they wouldn’t be enticed by just anything and it took a lot of line to get to them and a pretty good-sized lure.

Now he was fishing with a lure big enough to keep the juveniles off, but not big enough to catch the very large fish that would snap his line like dental floss.

As he reeled in toward shore, he felt the smaller fish bounce off the lure. He reeled faster to escape them and when the lure flashed toward the surface he saw the pollock, the one-pounders strike at the lure from all sides. They were in great competition but their enthusiasm faded as they neared the cliff and dispersed.

Down below Henrik could see the curious cod swimming vertical on the rock wall with their plantlike fins and disproportionate alien faces. There was apparent wisdom in those fish, beguiled by the stupidity of insatiable hunger. Henrik, in search of amusement, did not lift his lure above the water but instead dangled it by the seaweed covered wall and watched as a rust-colored individual circled. Momentarily, the fish’s jaw swelled and sucked the lure out of sight. At that moment Henrik yanked the unsuspecting fish clean out of the water and swung him up onto the bare rock face. The cod writhed and flopped around as Henrik tried to pin him to the rock. This was the trick of fishing the cliff. One had to be careful to not let the fish bounce back in the water taking the rod with it. To pin the fish to the rock and get the hook loose one needed both hands and possibly the pliers, which meant digging into coat pockets with fish fingers. But then smell of fish, of raw live salty fish, was another joy of life, something visceral in the face of clean and orderly books and cold computer displays. It was the smell of life, though Henrik still wished that he could dip his hands in the water, like in the bay, to get them clean again.

He got the cod loose, looked him in the eye, and flung him back down into the water. The startled fish landed stunned and uncertain before flicking his tail and fading into the depths. Would he remember the trauma being caught? Would it be burned into his animal mind like a failed love affair?

Though it was fun to catch the cod and no harm was done by it, Henrik told himself that he couldn’t afford any more games. Since he had been at the cabin, he hadn’t caught any decent fish, nothing he could brag about or take a picture of and show his friends or his brother. Those Oslo folks, what did they know about fishing, anyway? One had to be a Northerner to know about fishing. Well, if they didn’t appreciate it, it wouldn’t matter anyway. He had long since learned that things had to matter only to oneself in the end. If he caught a good-sized fish he would be happy. It would be his moment. Just him and the fish and life and death in the balance as it should be. Every man was essentially alone anyway.

He still remembered the reaction of his schoolmates when he had told them of his plans to spend a month alone at the cabin. Why the devil should he go north when he could stay and enjoy the frenetic summer nightlife of the capital, sail in Oslo fjord, swim at the popular beaches, have bonfires, picnics and backyard barbecues, and drink beer and tan in the park? Not to mention the girls that teemed in the streets in skimpy summer clothes with mischief in mind and temptation in every look and gesture. Then it dawned on them. Carefully they asked him, “Who’s going with you?” They named a few girls in class: the most probable and desirable candidates. They were hoping to be incredulous but he could not reward them. No, none of the above. He was going alone. He needed a break, some time for himself, peace of mind. “These are the last great days of your youth,” someone said. “You have all your life to take a break. This is not the time to take a break.” He pitied them for not understanding. It occurred to him that they were weak. They needed to continue the farce of endless parties and inane conversations, they needed to posture, to see and be seen in the right locales and social circles of the capital. They needed to hang onto the last shred of immaturity until it was stripped from their feeble fingers. They could not be alone with themselves or their thoughts. Silence made them uncomfortable and truth was something they avoided so as to not imperil their prosperity or expose the hypocrisy of the social system in which they lived. Henrik understood that it was common sense not to speak the truth, that it was better to be silent and stick with the status quo than to have an opinion. When he was in the city he laughed at jokes that were not funny, made conversation on subjects that did not in the least interest him, went to parties, bars, and events that he did not enjoy, and sacrificed his own sense of style to dress like his friends and strangers. That was why he needed to go North. He needed a break from faking it. He imagined that back in his grandfather’s time the common man probably had better things to do. Though he did not doubt that the aristocracy had it share of social posturing, one-upmanship, and codes of conduct to measure up to.

One never really knew a man until all his layers of sophistication were stripped away, Henrik thought, and one was forced to depend on him for survival under difficult circumstances. Henrik did not place much faith on the ability of his so-called friends and future competitors at the university to survive in the elements. Such people were, if not a bore, a liability dependant on suffering each other’s excesses and eccentricities.

What the hell, he thought. Give me these mountains and this ocean any day before I have to humor a man for my own well-being, or sacrifice my energy to support another’s shortcomings.

The sun was just below the horizon now and it was still light, not blinding but dusk light, open light that helped a man see himself clearly. Henrik gave another satisfying cast out into the ocean, heard the plunk, and let the line play out off his reel. He reached into his coat and produced the flask of homemade spirits. Pinning his rod against his body, he unscrewed the cap and lifted the bottle to his lips. The clear liquid burned nicely in his throat. A wind had picked up rippling the surface of the water and he knew the best protection would be the warming sensation of the liquor that would soon spread to his limbs from his belly. He put the bottle away, clicked the safety of his rod into place, and turned the crank slowly. Sometimes he would simply reel in at a steady pace, at others he would reel and jerk on the line. He was not sure of the fish’s preference, but both were satisfying to him. Just as with lures, sometimes effectiveness was secondary to a fisherman’s aesthetic sensibilities.

Out in the fjord he noticed that the water had begun to bubble, an effect entirely different and separate from the rippling effect of the wind. He had seen such an event many times; it was precisely the reason for his fishing at that time of day and also in the morning. Soon birds appeared on the horizon, not just scattered birds but a large flock. The bubbling water began to boil. Henrik saw the first few fish start jumping out of the water. The birds hovered above the jumping fish and fell into the water one after another pulling their wings in as they struck the surface; they dropped in waves into the frothing agitated ocean. The panic of the fish seduced them and they dove relentlessly unable to control their hunger. Henrik watched a boat emerge from the bay and round the point. He was not close enough to identify the men inside. He thought to wave but they grew distant as they motored to the source of the commotion.

The forage fish: the sardines, herring and juvenile pollock didn’t have a chance. They were besieged on all fronts. The dolphins had circled the fish with their sonar, and were knifing through the mass; the large pollock and cod were coming up from below pushing the fish right out of the water; the birds were dropping down and picking up the panicked leftovers. Damn, I wish I had taken the boat, Henrik thought. The feeding frenzy was maybe a quarter mile offshore, frustratingly out of reach.

The ocean was very deep below him. He realized after a few casts that he might not have enough line to reach the big fish anyway. He cast several times and watched the horizon as the white-yellow ball met the water and blurred with it. Henrik squinted as the water turned golden and radiated the sunlight across its surface.

He reeled in and there was a strike on the line that reverberated in his heart. He pulled on the rod and his excitement subsided. His emotions were calibrated by weight and this fish, a pollock judging by the fight, was not very large. Still, he had caught it at a good depth and it would provide some distraction from his mind; it would take him away from the future and the past and into the moment. He reeled part way in before his pole jerked down abruptly and grew heavy. The other fish must have gotten off and been replaced by a pondering cod, heavy like an inanimate object and not a fish at all. He worked the fish careful not to lose his line, bringing him ever closer to the shore, until suddenly he appeared, that wonderful moment when predator and prey look each other in the eye from the abyss of survival. Henrik watched him and thought, cod is good eating and this guy’s not bad size; if he were any smaller he wouldn’t taste right, especially not at this time of year. The fish was now a few feet offshore and Henrik thought about where it would be best to pull him up, a spot where the cliff sloped nicely and he could edge a little closer to the water line. But then the cod simply opened his mouth and released the pollock he had held onto with such patience, realizing that the predator above had the upper hand, as he neared the cliff and the point of no return. There was a limit to a cod’s appetite, after all.

Henrik thought of life briefly as a series of containers, one smaller than the next, all of which were contained in one large vessel. That was the food chain and the web of life splintered and cracked as it was by man’s attempt to alter it to his own benefit. A hopeless effort, really, as man was only a minor container swallowed eternally into something larger than himself.

When the cod let go, Henrik laughed out loud. He hauled the poor pollock up the rocks, unhooked him, held him like a microphone at eye level and said, “this is your lucky day, little guy. Who knew that being caught would save your life.” Then he tossed him back into the water and gave another cast. He drank again from the fifth, and as the line played out, he reached into his other pocket for the chocolate, broke off an uneven chunk and savored the bitterness in his mouth. It certainly doesn’t take much to enjoy life though they’d have you believe otherwise, he thought. It’s only when you get away from the city that you can see clearly the confusion that is its centrifuge. Why did everyone so badly want to be in the center and why did he gravitate toward the margins and solitude? Was it just a case of misanthropy?

This time he intended to let the line play out completely all the way to the core of the reel. The big one was out there, the wise fish and his nemesis, and he would feel him out, sooner or later the temptation would be too great, the desire to grow larger and more powerful pitted against the possibility of being destroyed by that same drive to greatness. He reeled slowly and marveled at the ocean’s depth. He wondered how much line he needed to reach the bottom and he hoped that he would not snag up as his line reached the shore.

You are very lucky to be alive, he told himself. You are lucky to be able to see the midnight sun and smell the salt air and stare at the mountains that surround you. And you are so small, why if you disappeared it would go unnoticed. The only difference would be the absence of that pinprick of light from the cabin at night and the puff of smoke from the fireplace in endless nature and the greatness of the sea.

It hit and it was the big one. It did not matter how many fish a man caught in his life, each was like the first time. Certainly, there would always be a few fish that would forever remain in a man’s memory for their size and their struggle. Such it was with men as well, though with less honesty. The fight with man was fraught with betrayal, plotting, cowardice and hypocrisy. Not so the struggle of a fish. If the hook came loose that was luck, no more, no less. The fish that got away did so on merit not on deception, substitution, or favors.

Henrik told himself now that the fish on his line was not going free. He realized immediately the limitations of his situation. His line was too light for the fish. He would have to let him run at all opportunities and reclaim the line when his prey grew tired. Also, he would have to set the drag carefully to tire to fish out but not tight enough to snap the line. Then there was the question of getting him up the rocks. Impossible. Even though Henrik had fished there a thousand times, and knew full-well that a fish of any size could not be lifted the three or four meters up the cliff, the realization that he would have to climb down to the waterline was always unpleasant. Still, he did not worry much about bringing the fish up. It would take some time to wear him out and also to recover an entire reel worth of line. And while the fish fought against the invisible, Henrik wondered at his appearance and longed for the moment when he would come to the surface and show himself and break the spell of the unknown. Fighting that fish, he grew to love him. At that moment the fish was the sole provider of his life’s purpose and Henrik was deeply grateful for having caught him in all the emptiness and veiled meaning that was the ocean and man’s life in general. There was an unconscious gratitude in him for having escaped the self-consuming labyrinth of his own reason; and without the fish that was not possible and certainly not with other people who were so frustratingly conscious. Have I caught the fish or has he caught me?

And the fish, a pollock with the fight that made him grow to epic proportions in Henrik’s mind’s eye, what was he thinking? What would a man think when he was caught in something inevitable like his own death, like his grandfather dying of cancer after having fought the good fight: fighting that unavoidable truth that justified life’s struggle?

After an hour of careful reeling, of seemingly endless give and take, Henrik recovered the majority of his line. His heart hung in his throat at the thought of seeing the fish for the first time. He reeled and managed the frenetic jerking with the anticipation that one feels at seeing a long lost friend or lover. It was the anticipation of reunion with history. And when the fish came into view he was more noble and beautiful than Henrik could possibly imagine: a large silver torpedo with its haunting aquarian gaze and the face of a poker champion. Henrik was beside himself with excitement. He reeled him carefully toward shore, the pollock by now resigned and putting up little resistance as it came like a cruiseliner into port.

Welcome home, welcome home, my long lost friend. How I missed you. How wonderful to see you, you beautiful little beast.

Then the unexpected happened. As he pulled up on the rod, the fish gave a last jerk and snapped the line. Henrik’s heart dropped like a stone in the sky. He was devastated. And to add to his frustration, the fish did not swim away immediately. No, he floated there, moving his fins in a careful way, his gills pumping desperately for oxygen after being dragged fighting through the ocean for nearly an hour. Henrik imagined the fish was mocking him, or perhaps sizing him up before he disappeared. That fish would carry away a lesson and a knowledge that separated him from his peers. If only he could remember, then he would be immortal.

Good-by, fish. Good-by. May you prosper and have a nice life.

Henrik felt the urge to jump in and grab the fish in his hands before he escaped. It was an illogical thought, he knew, but it was all that he had to fill the short distance from where he stood to the water where the fish floated for an aggravating duration. To add to his dismay, in the corner of the fish’s mouth was his trophy, the silver lure with the blue strip that he had inherited from his father who had fished it for the first time thirty years before him. No, that was not how he expected the day to go. All his hopes were dashed. And, as if to confirm his thoughts, the fish finally flicked its tail and disappeared into the depths.

Henrik sat down on the rock, removed the bottle from his pocket and took a long drink. He considered that it was time to go home. Well, it was a beautiful moment, anyway. Even without the fish he wouldn’t go hungry. He sat there a while longer and contemplated the ocean and let himself calm down. His heart was pounding from the encounter and he was shocked by the loss.

Then, as he was gathering his things to go, the incredible happened. The fish returned from the deep, exactly to where he had been several minutes before. When he was nearly to the surface, he turned on his side with his one eye staring up at the sky above. His gills were moving rapidly as before and Henrik’s heart filled with joy and pity at once. The fish had come back to die. The fight had taken everything from him. He did not have the will to live any longer. But still there was the chance that he would recover and escape, or even that he would sink or the current would take him away. Henrik could not stomach the thought of having the fish die and sink into obscurity. It was too much to tolerate. They were linked and Henrik had to bring him up on land and put him out of his misery at all costs. He had to eat that fish and complete the circle. Never would a meal taste so good to him or have as much importance.

He fumbled with his line to tie on a new spinner. With great difficulty, he looped the line through the eyelet and tied a knot. His hands were shaking with excitement as he cast repeated looks to the water to verify the fish’s location. Sure enough there he was, prized lure and all, waiting to be salvaged. Henrik attached another lure and cast into the water with the intent of snagging the fish. After several attempts of dragging the lure by the fish, he gave a jerk and hooked into his jaw. He walked along the shore to find a suitable place where he could descend to the waterline. He dragged the fish for twenty or thirty yards laterally until he found a spot where the cliff sloped and formed a cleft packed with seaweed and the occasional boulder. It was an extremely difficult descent given the steep angle and the seaweed. Once he stepped on the slick seaweed, lost his balance and fell, sliding to a stop against a boulder. His heart was pounding and there was one thought in his mind: land the fish. Finally, after careful steps he made it down to the waterline and dragged the fish to his waiting hand. There he comes, just a little farther now, easy does it. Henrik grabbed him by the gillcover and hauled him up the cliff careful not to lose his balance.

He returned to where he had left his tackle. The fish gasped in his grip and he took his knife from the belt loop and slit its throat just under the gills. A ribbon of blood ran down the rock face toward the water. To Henrik that blood was thick with meaning, knowledge, and truth. He cut into the fish’s spine and folded his conical head back like a cookie jar, heard the crack of bone and broke the head clean from the body with brute force. During this process his hands were visibly shaking from excitement and the violence of his actions. He slit open its belly, pulled the guts out and exposed them steaming to the air. Everything smelled of death. The polished fish head stared at the sight of its entrails distant from its body. Henrik threw the guts into the water and stared at his bloody hands. He smelled them before wiping them on the nearby brush. When he bent over to collect his tackle, he accidentally stepped on the contemplative fish head, lost his balance and slid down the cliff into the water.

He was in the ocean with all his clothes including his jacket and boots with the dressed fish on land above him. The water was cold and it sucked his breath away. Shock had not yet been taken over by fear. Nor did the comedy of the situation occur to him. I’ll just get these clothes off and swim to the cliff, he thought. But then he hadn’t reckoned with the current that carried him away from land. He struggled to keep himself afloat with the weight of his clothing. He felt the downward pull of the current and realized that he would not be able to reach the cliff face. Fear filled his mind along with anger. His head dipped under the water as he fought the current. His grandmother’s warning echoed in his mind. He was never more painfully aware of the distance between himself and his grandfather who would never have drowned in such a way. He thought of his father fishing on the cliff and the prized lure that he had saved. He thought of the fish that he had killed and that would kill him and also how far he had traveled for solitude and his own untimely death. Everything he had believed about the vastness and the indifference of nature was true. He had been linked inextricably to the fish in all that wide ocean and now he was sinking into the same depths the fish had abandoned. Both would die in the other’s home; fate had forced them to trade places.

Henrik’s body continued to struggle against his reason and his predicament. If only he had brought one of the girls or a friend from school with him, then it would not be his last day. His own desire for solitude and independence from the shortcomings of his fellow man had proven fatal. His struggle was doomed to failure and his screams were heard by no one. Finally, unceremoniously, Henrik dipped below the water like the sun with the fish head as his only witness.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, consider

donating to support my writing.

A donation wil also provide password access to exclusive content via the Exclusive menu button.

- Markus